Wed, Feb 18, 2026

Interactive Technologies: A Guide to Choosing the Right One

Are you designing an interactive experience for a museum, training, retail space, or event? Wondering which technology to use? This guide is for you. We wanted it to be useful, honest, and accessible, even if you’re starting from scratch.

Before Talking Technology, Talk About Your Audience

It’s tempting to start with the technology. But the real first question is this: what is your audience willing to do?

Take out their phone? Scan a code? Touch an object or device? Do nothing?

Each requested action requires an investment from your audience: in time, attention, and trust. The higher that investment, the more your content needs to be worth it. However, the smoother the interaction, the more likely it is to be adopted by everyone.

Keep that balance in mind for what follows. That’s what will guide you to the right technology, far more than the technical specs.

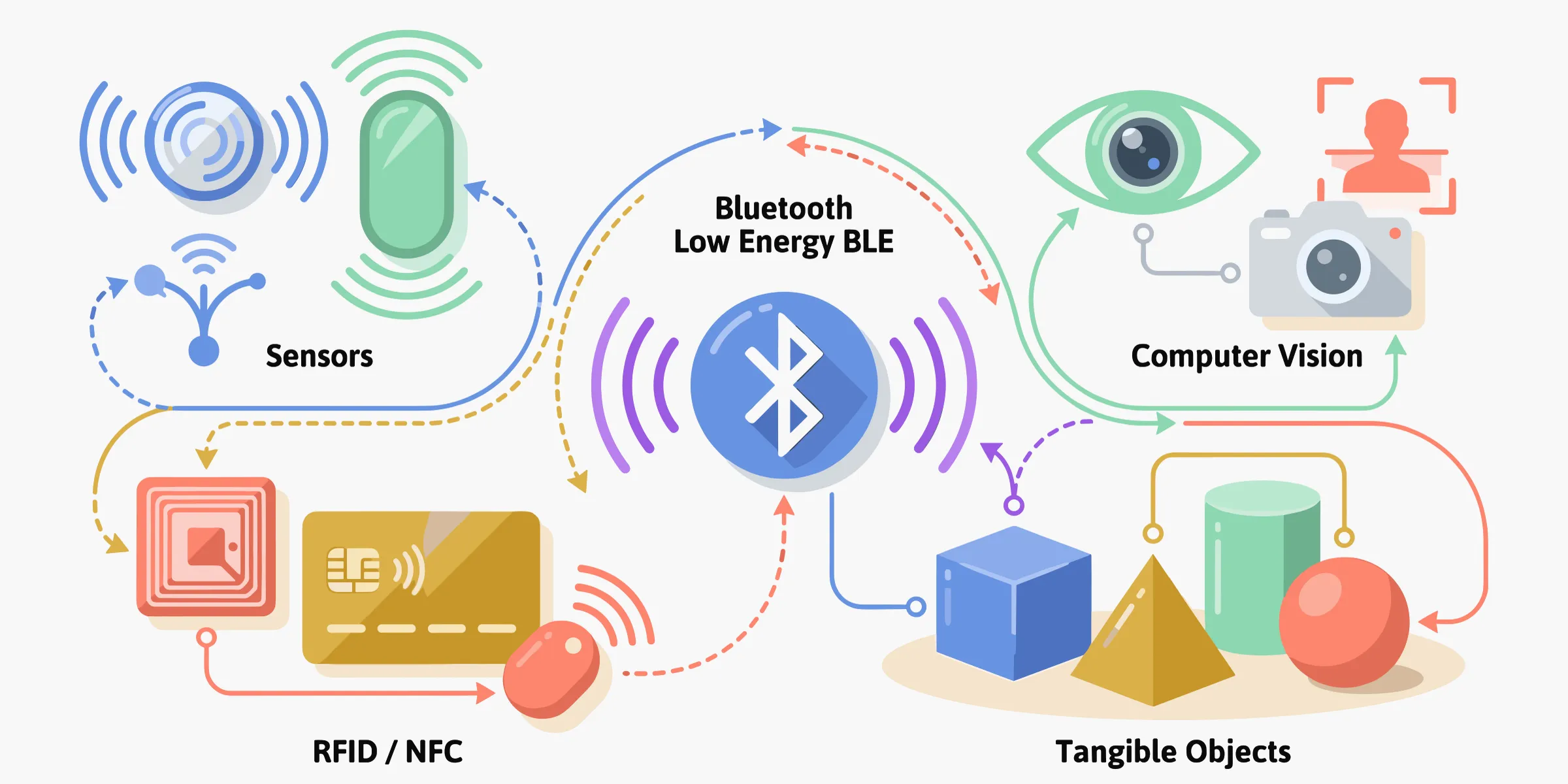

The Main Families of Technologies

Interactive technologies can be grouped into four main families:

- Tags and codes: trigger an action with a simple gesture

- Proximity: trigger automatically, with no gesture

- Vision: use the camera as a sensor

- Tangible objects: when the object becomes the interface

Each has its own logic, strengths, and limitations. None is “the best”; there are usage/constraint combinations that work, and others that don’t.

We won’t cover screen-based interfaces here (touch kiosks, interactive tables, projection): that’s a separate topic that involves ergonomics as much as technology. If that’s your need, see our guide on interactive kiosks: What Is the Best Software for Interactive Kiosks?.

1. Tags and Codes: Trigger an Action with a Simple Gesture

The user interacts with a physical marker (a code, a chip, a tag) to access content. It’s the most common entry point and often the most underestimated.

QR codes

Not much to explain: everyone knows them, they cost nothing, and they work on all smartphones. For many projects, they’re the right default choice, especially if your audience has time to scan and you don’t want to require downloading an app.

The downside: in a fast flow, the effort of taking out a phone and framing the code is enough to put off some people. And a poorly lit, damaged, or too-small QR code becomes a friction point instead of an entry point.

NFC (Near Field Communication)

You place your phone on a tag, and the content triggers. No app to open, no need to frame anything. Range is very short (a few centimetres), which avoids accidental triggers.

The chips are tiny, battery-free, and can be embedded anywhere: in a museum label, packaging, a badge, a plinth. It’s discreet, fast, and when it’s clearly signposted (a small icon is enough), people understand immediately.

The real issue with NFC is compatibility. Android is fairly open. iOS has improved a lot but remains more finicky depending on model and version. Before building an entire journey around NFC, test on the devices your audience actually uses, not on your team’s latest iPhone.

RFID

RFID is the broader family that includes NFC, but it operates at a different scale. Longer range (several metres depending on frequency), reading multiple tags at once, automatic identification with no visitor gesture. On the other hand, it requires dedicated readers that you install in the space.

It’s the technology of choice for identifying objects in flow: access badges, tokens in a journey, tracking items. To dig into the differences between RFID frequencies and their practical implications, the GS1 organisation’s guide is a good resource.

One thing we often see in the field: RFID that detects “too well” can become a problem. If the reader picks up a tag you didn’t mean to activate (because it’s in a visitor’s pocket as they walk by), you get phantom triggers. Reader placement and range need to be calibrated carefully.

What these three technologies have in common: the more “invisible” the tag is to the user (NFC built into a plinth, RFID in a badge), the more you need to compensate with design: clear signage, an immediate response that confirms “got it”, and behaviour that forgives mispositioned objects.

2. Proximity: Trigger Automatically, No Gesture Required

On paper, this is the most appealing family: content triggers on its own when the user enters a zone or approaches an object. No scanning, no touching, no need to take out a phone.

In practice, it’s also the family where the gap between promise and reality is often the largest.

Beacons (BLE beacons)

Small transmitters that broadcast a low-energy Bluetooth signal. The phone picks up the signal, and the app reacts based on proximity. Offline operation, low cost, iOS/Android compatibility: we’ve written an article on the subject: What is Beacon Technology?

What matters in the context of this article: beacons identify zones, not exact positions. And on-site calibration is non-negotiable.

We regularly support exhibition audioguide creators in this phase, and the finding is always the same: the initial deployment plan never survives the first on-site test. Walls reflect the signal differently than expected, two neighbouring rooms “talk” to each other, a metal pillar creates a dead zone. That’s normal, but you need to plan time on the ground to adjust.

UWB (Ultra-Wideband)

UWB is the heavy artillery of indoor positioning: centimetre-level accuracy, real-time positioning. If your project requires knowing exactly where someone is in space, it’s the reference.

But let’s be clear: it’s a whole other level of investment. Dedicated infrastructure, compatible devices (not all smartphones support it), deployment and maintenance complexity. UWB is justified when accuracy is a non-negotiable functional requirement.

How to choose between the two? If “the user is in this zone” is enough, beacons do the job. If “the user is exactly here, 12 cm from this object” is required, look at UWB. For the vast majority of projects, beacons are sufficient.

3. Vision: Using the Camera as a Sensor

This is the family that’s most impressive in demos and most demanding in real-world conditions.

Image recognition

Point your phone at a work of art, a poster, or packaging, and the associated content appears. No QR code, no tag: the object itself is the trigger. Elegant when the scenography must not be altered.

On the other hand, it requires good-quality reference images recorded in advance. And real-world conditions (reflections, viewing angles, changing light, visitors walking in front) can seriously complicate detection. Test in the actual conditions of the venue, not in a well-lit office.

Visual markers (ArUco, AprilTag)

Small square patterns, a bit like QR codes, but designed to be detected very quickly and to indicate the camera’s position and orientation. Less elegant than image recognition, but much more reliable. The pragmatic choice when detection stability matters more than aesthetics.

Gesture and motion detection

Interact without touching: raise a hand, turn your head, approach. Spectacular when well calibrated, frustrating when it doesn’t work.

The problem is usually not the technology, but the interaction design. If the requested gestures aren’t natural, people give up. Field constraints are numerous: light changes, visitors get in each other’s way, the system drifts after equipment is moved. And a camera captures images of people, which raises privacy questions. Prefer on-device processing and capture only what’s strictly necessary.

Before going down this path, one honest question: “Can we achieve the same result without a camera?” If yes, compare seriously.

Some devices also include depth sensors (LiDAR, 3D cameras) that measure volume and distance more reliably than a standard camera. A plus for augmented reality and immersion, but hardware-dependent and more complex to integrate.

4. Tangible Objects: When the Object Becomes the Interface

As soon as you put an object in someone’s hand, the game changes. You move from “I click” to “I manipulate.” It’s often more memorable and more inclusive, because the gesture is intuitive.

Some interactions that work very well in the field:

- Placing or removing an object: a clear, binary state (“placed = activated”). In a museum, it might be a token placed on a plinth to display the corresponding content.

- Rotating: a progressive control, highly intuitive (like a volume knob). In training, it can be used to move through the steps of a procedure.

- Moving: explore, associate, compare. In retail, lifting a sample to trigger a product video.

- Using an object as a “key”: each visitor receives a different object, and the experience adapts.

These gestures work because they don’t need instructions. You see the object, you understand what you can do with it.

To dive deeper into this topic (multitouch tables, the TUIO protocol, practical use cases), see: Object Recognition on Multitouch Tables: Uses and Technologies.

For it to last, three things matter: an immediate response when the user acts, tolerance for imperfect gestures (object askew, upside down, moved too fast (it shouldn’t crash)), and a plan B when the object disappears. Because an object handled by hundreds of visitors gets lost, broken, or pocketed. Plan for it from the start.

Feedback to the User: What Makes an Experience Hold Up

We talk a lot about detection technologies. But what makes the difference between “it works” and “it’s pleasant” is the feedback you give the user after their action.

A sound, a vibration, a light that turns on: that’s what confirms the gesture was understood. Without that confirmation, the user doubts, repeats the gesture, and you get double triggers, frustration, and phantom bugs.

And think about accessibility. Content that’s only audio excludes people who are hard of hearing. Subtitles, transcripts, icons: it’s not optional: it’s what makes the experience work for everyone.

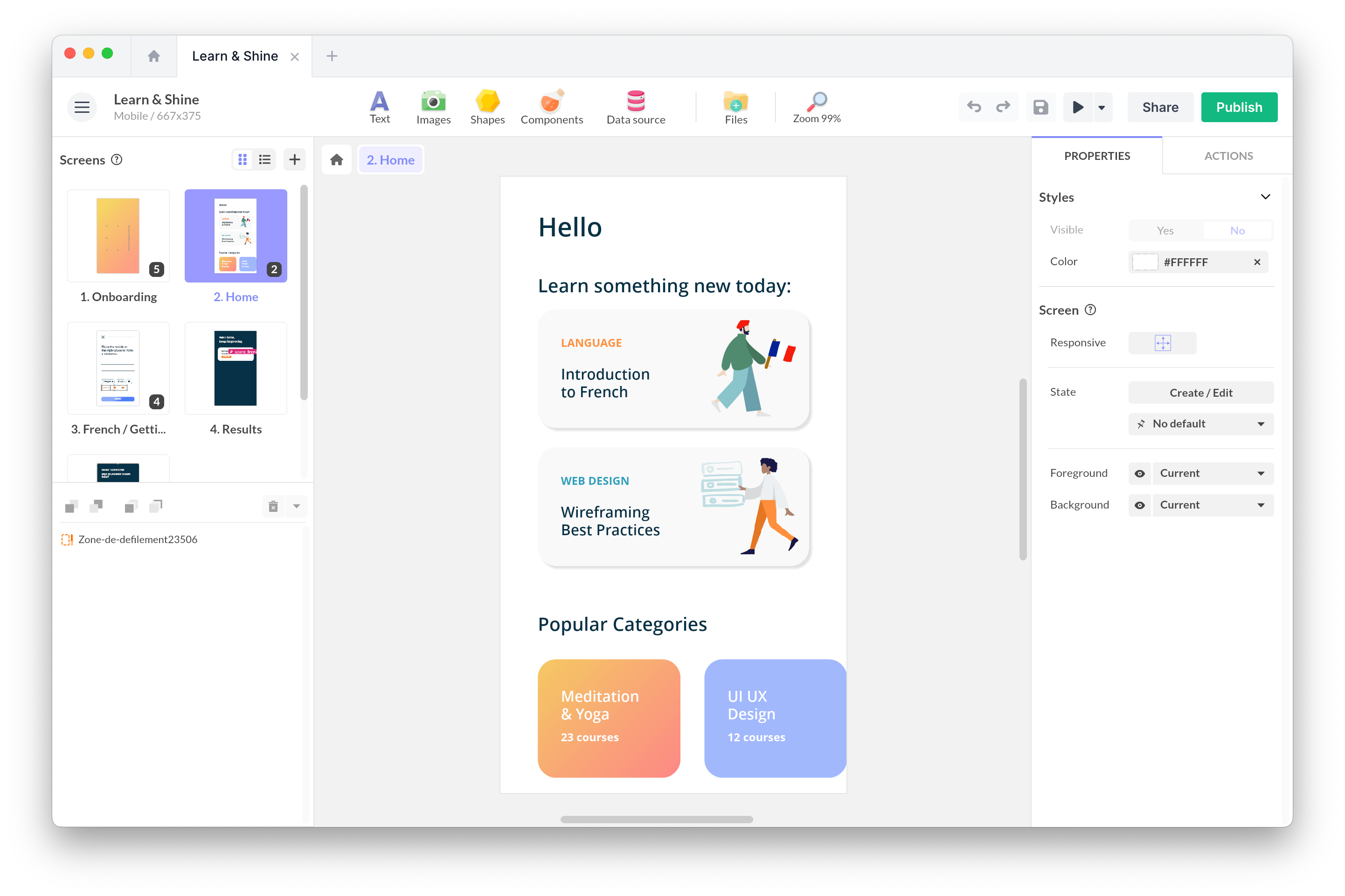

What You Can Do Without a Developer (and What Will Need One)

This is a point we rarely bring up, but it often determines a project’s success.

The most common technologies (QR codes, NFC, BLE beacons, image recognition) can be integrated into an app without writing code. That’s what we do with PandaSuite. Multi-screen setups and physical object recognition are too, even if implementing them requires more technical rigour (hardware setup, TUIO protocol, calibration).

On the other hand, some technologies still require custom development: UWB, camera-based gesture detection, specific sensors embedded in objects. PandaSuite can serve as the foundation for the experience, but those building blocks will need additional technical integration. Budget, timeline, and maintenance follow.

Our advice: start with what you can prototype yourself. Validate the journey, test the content, measure your audience’s engagement with accessible technologies.

If the need for a more advanced technology is confirmed in the field, you’ll have real feedback rather than assumptions. It’s less spectacular, but that’s how you avoid projects that cost a lot and nobody uses.

How to Choose? The Right Questions to Ask

Rather than a complex comparison table, here are the questions that really matter:

“Does my audience have time?” If yes, a QR code may be enough. If the flow is fast, favour NFC, beacons, or automatic detection.

”Does the experience need to work without the internet?” NFC, beacons, and embedded content make you independent of the network. That’s a real advantage in many venues.

”Who will maintain the installation?” A QR code is almost zero maintenance. Beacons need battery changes. A vision system needs recalibration. Be realistic about the resources available after launch.

”Is the interaction accessible to everyone?” Height of devices, text size, alternatives to sound, required gestures… Consider the diversity of your audience from the design stage.

”Are we capturing personal data? Is it really necessary?” An NFC tag or QR code captures nothing by default. A camera or Wi-Fi can. Ask yourself before, not after.

And when two options seem equivalent, choose the one with the fewest dependencies (network, calibration, pairing) and that will best survive imperfect use. That’s almost always the best choice.

In Summary

A good technology choice isn’t the one that impresses the most. It’s the one that makes a journey obvious, reliable, and maintainable.

Three habits that make a difference:

- Limit the number of technologies in a single journey. Each added technology is a potential point of failure. Two or three complementary technologies is often the right balance.

- Favour usefulness and accessibility over the “wow” effect. Spectacular wears off quickly if it doesn’t work well.

- Document operations from the start. Who recharges? Who replaces? Who recalibrates? How is content updated? These questions are as important as the technology choice.